During the summer of 2020 following the death of George Floyd, calls for police reform echoed across the country, including around the issue of cops in schools. Activists called for change in the use of school police, also known as School Resource Officers (SROs). Concerns about the school-to-prison pipeline and its racially disparate impact on black and brown youth sparked a national conversation on the role of policing in America’s schools. As more than three years have passed since the heightened calls for police reform began in 2020, it is important to examine how these movements have impacted policing in schools. The goal of the present report is to understand the movements for reform and policy changes around cops in schools that emerged following the Black Lives Matter movement in Chicago and other major U.S. cities.

The Impacts of Police In Schools

The use of police officers in school discipline is widespread in the United States, with nearly 60% of schools reporting having an SRO as of 2018.1 The impacts of cops in schools on student discipline are well-documented in the literature, including that increases in the number of SROs are associated with increases in the use of suspensions and expulsions.2 One study also found that having an officer present led to a 400% increase in the number of student arrests for disorderly conduct.3 Although supporters of SROs cite their importance to school safety, studies show there is no evidence that school police affect school crime rates, school safety, or gun violence in schools.4 Further, racial minority students and students with disabilities are more likely to be suspended, expelled, and referred to the juvenile justice system.5 One study also found that 40% of SROs had not received any specific training on school-based policing,6 contributing to a concerning picture where cops in schools do not positively contribute to school safety but instead exacerbate the school-to-prison pipeline, particularly among marginalized student populations.

The Present Report

This report examines the use of cops in schools since 2020 across 30 of America’s largest cities. These cities were selected by population size, and for cities with multiple school districts in their metropolitan areas, the school district directly covering the city itself was chosen for analysis. In each city, we tracked reform movements around SROs as well as changing school district policies and spending toward police in schools. We also examined how high-profile school shootings have impacted school security policy among these 30 cities. Particular attention is also paid to the developments around SROs in Chicago, with recommendations for transparency and reform suggested. All the data used in this report comes from publicly available school-district data and news media sources.

It is important to note that the structure of school policing varies among the cities in our sample. Some of the top 30 cities have direct contracts between their school district and their local police department for officers, including Chicago Public Schools’ contract with the Chicago Police Department,7 while other cities’ schools run their own internal school district police force. Additionally, cities refer to their school police by varying names, such as New York City’s team of “School Safety Agents” that are NYPD officers.8 We included all of these structures of school policing in our analysis, and throughout the report refer to them all as ‘School Resource Officers’ as this term captures their shared function as armed police in schools.

School Police in Chicago since 2020

As mentioned above, Chicago Public Schools (CPS) contracts with the Chicago Police Department (CPD) for armed School Resource Officers. Prior to 2020, Chicago had a $33 million contract that placed school police officers in 72 schools.9 In the summer of 2020, CPS students and activists organized around a motion to remove SROs from Chicago schools, sending more than 30,000 emails to board members in support of terminating the contract, organizing meetings with nearly every board member, and holding dozens of rallies. The student coalition #CopsOutCPS was particularly influential in this process and cited racial disparities in school-based policing in their efforts.10 In the first split vote of the Chicago Board of Education in decades, the board decided to keep their contract with the police. Each school’s Local School Council (LSC), an elected body of teachers, parents, and community members, would instead decide on the number of police they wanted in their school, ranging from two officers to none.11

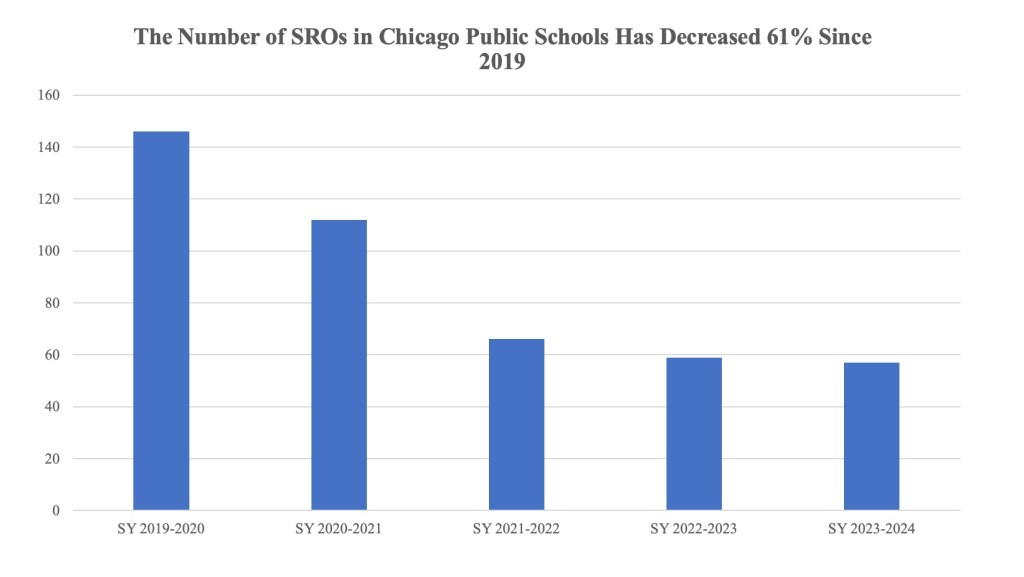

In these 2020 LSC votes, 17 schools opted to remove both officers, and to ensure preparedness in the absence of these officers, these schools created alternative safety plans for emergency response.12 Criticisms emerged that the LSC meetings were not readily available for public viewing13 and that schools were not given the option to spend the extra funding from removing SROs elsewhere, potentially influencing decisions to keep officers.14 Further, following these votes, Black students remained more likely to attend a school with an SRO than their Latino and White counterparts in CPS. This is especially concerning in light of research showing that in 2015, Black students made up 70% of CPS’ in-school arrests.15 Ahead of the 2021 LSC votes on SROs, CPS let schools receive $50,000 in funding for alternative safety options when they voted to remove an officer, but some LSCs were not informed of this.16 Despite these criticisms, LSC voting remained in place until 2024,17 and under this system the number of officers in CPS continued to decline as schools voted to reduce or remove officers. As the graph below shows, the number of cops in schools in Chicago decreased 61% between 2019 and 2023.

These decreases in the number of cops in schools are particularly significant as research has found that in Chicago, students who attended a CPS school with an officer were 4 times more likely to have the police called on them than students who did not have an SRO in their school.18 Further, in the 2021-2022 school year’s first semester, CPS high schools called police on students 38% less often than in the first semester of the 2019-2020 school year, with the reduction in SRO presence potentially aiding this decline.19

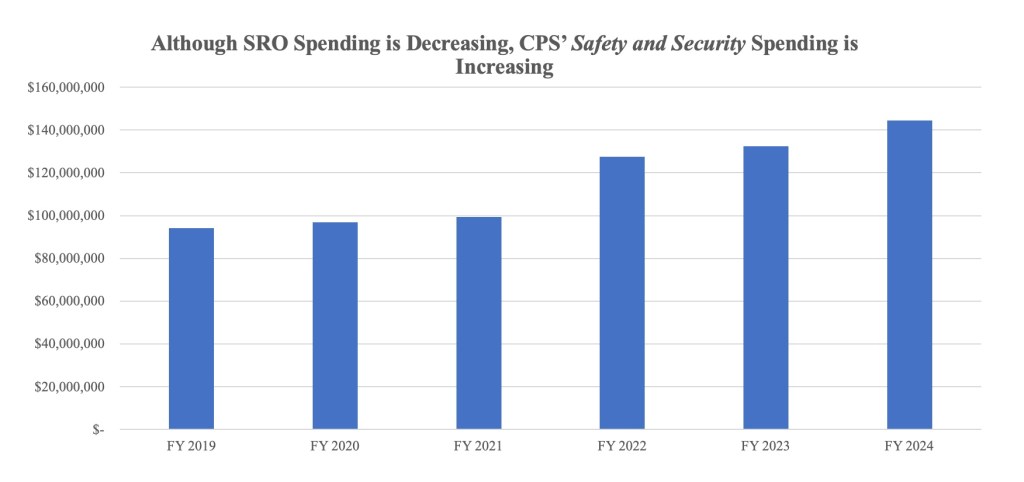

In addition to the lower number of SROs in Chicago schools, the contract between CPS and CPD has also changed since 2020, both in financial scale and in SRO policy. In addition to a reduced budget due to the LSCs that removed officers, CPS also decided in 2020 to no longer fund mobile patrol officers that formerly assisted schools without SROs.20 These reductions, in combination with budget credit for school days that were virtual due to the COVID-19 pandemic, led to a large reduction in the SRO budget from $33 million in 2019 to $12 million in 2020.21 As LSCs continued to reduce their use of officers, CPS’ spending on school police continued to decline, with a 69% reduction between 2019 and 2023 (see graph below).

Further, CPS’ new 2020-2021 contract for SROs included several policy reforms, such as stricter eligibility criteria where only officers with excellent disciplinary records can work in schools, prohibiting SRO use of gang databases, increased training for officers, and the creation of behavioral health teams to provide a holistic approach to school safety.22 CPS also announced the creation of Whole School Safety Programs, which included collaborations with community organizations to create trauma-informed safety policies as alternatives to cops in schools.23

Additionally, the Mayor and CPD formed a 2020 working group on SRO policy that wrote 54 recommendations to improve the SRO program.24 Although 35 of these recommendations were either already addressed under CPD’s contract or out of CPD’s scope to implement, CPD accepted 16 new recommendations and rejected 3. Two of the recommendations rejected were about officer complaints, for which CPD said they would not change their current complaint process, while one asked that SROs not access police databases for student information, which CPD claimed was necessary to ensure public safety in schools.25 Further, although 16 recommendations around topics like confidentiality protections and interviewing of students were accepted, some were significantly modified, leading to frustrations from activists and some working group members.26 For example, the working group asked that SROs “not handcuff or use other physical restraints on a student in a school,” which CPD modified with the added language that SROs will “ensure any use of force or use of restraints are reasonable and necessary.”27 The group also recommended that if a student has to be detained it must be in a way that “minimizes visibility to the school community”, which CPD agreed to do but only “when it is safe and feasible to do so.”28 More recently, changes have continued to be made with the 2022-23 contract requiring increased SRO training on restorative justice, racial bias, and interacting with students with disabilities.29

As previously mentioned, in February 2024 the Chicago Board of Education voted to remove all school police by the start of the 2024-2025 school year. This means the remaining 57 SROs in Chicago Public Schools will be removed, marking a win for activists who have been pushing for this decision since 2020. As part of this change, the district will also make a holistic school safety plan that includes increased funding for restorative justice programs.30 Some expressed concerns that Local School Councils are no longer making the individualized decision for their school of whether to keep or remove officers, while the Chicago Teachers Union expressed support for the Board’s decision.31

Although Chicago’s spending on cops in schools has declined and will soon cease, CPS’ safety and security spending is on the rise (see below graph). CPS’ Office of Safety and Security includes not only SROs, but also safety communications, technology like security cameras and metal detectors, clinical and crisis teams, and crossing guards.32 Schools that remove their SROs are able to ‘trade-in’ the previous SRO funding into funding for a new position, and some schools choose to hire unarmed ‘security officers’ in their place, who are not law enforcement agents but are also included in this safety and security budget.33 Although many parts of safety and security are vital aspects of CPS, the inclusion of security officers and school surveillance technology within this office necessitates this closer look. For example, in July 2023 CPS approved a $1 million contract to purchase approximately 70 modern X-ray machines to replace the older models already in many schools’ entryways.34 This school security component has received pushback, with opponents citing research on possible negative correlations between surveillance levels and academic achievement.35 As activists continue to push for change around school policing, it is vital that the focus is extended beyond just SROs toward these other aspects of school security.

School Police Reform Nationwide

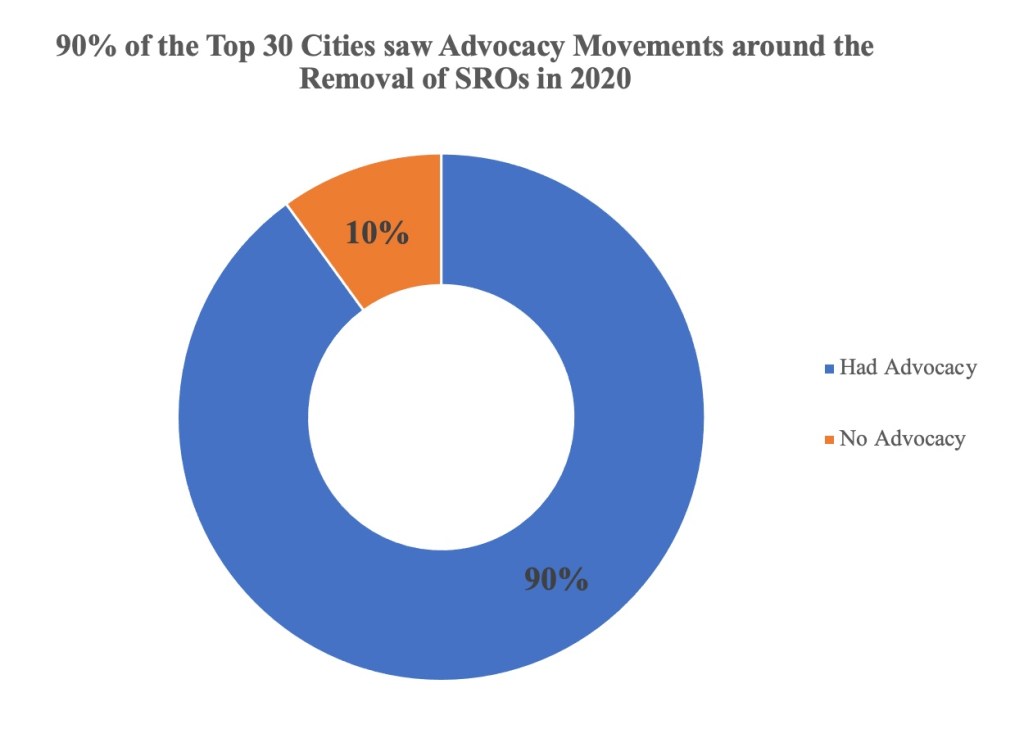

To put the changes around cops in schools in Chicago in a greater context, it is important to examine the post-2020 changes around school police on a national scale. The summer of 2020 saw reform movements around school policing not just in Chicago, but across the country. 27 out of the top 30 cities analyzed (90%) saw advocacy efforts to remove or reduce SROs from their schools. Many cities had protests organized by student-led groups, such as the “CPD out of CCS” movement in Columbus, Ohio, the Charlotte Liberation Party in Charlotte, North Carolina, and Defund School Police SD in San Diego, California. Student groups often received strong community support, with the Philadelphia Student Union’s petition for the removal of SROs gaining 13,000 signatures36 and Seattle’s student petitions to end the district’s partnership with local police gaining over 18,000 signatures.37 In some cities, community and justice organizations also got involved in the advocacy process, such as Safer Schools Nashville, a grassroots organization that called for the removal of SROs,38 and Austin Justice Coalition, a community organization that published resolutions for school police reform.39

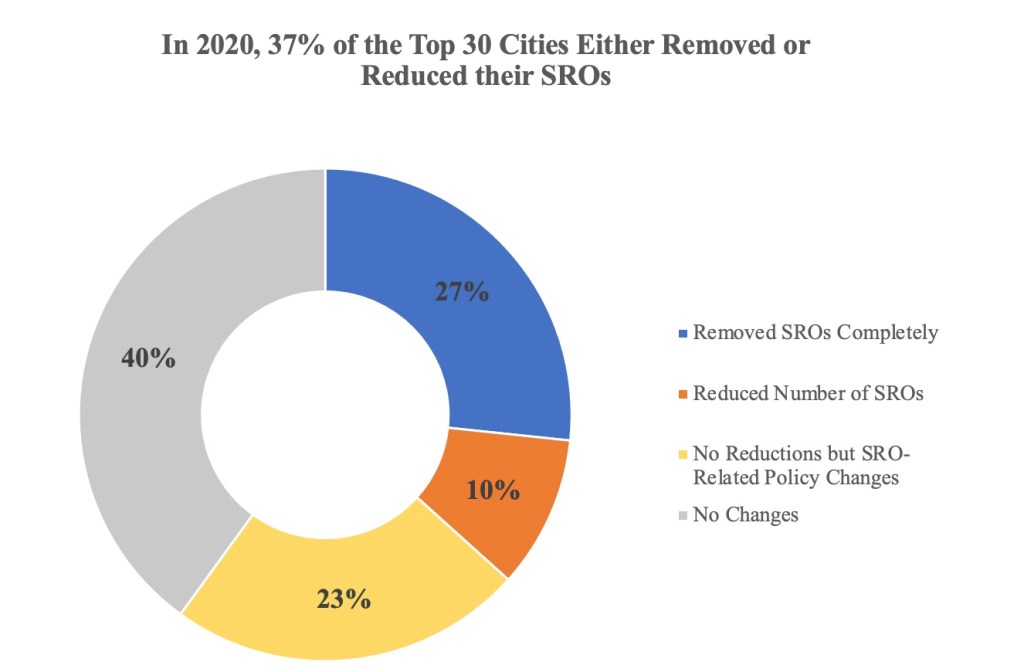

As a result of these 2020 advocacy movements, 11 of the top 30 cities (37%) voted to either reduce their number of SROs or remove them entirely from their schools. The 8 cities of Minneapolis, Portland, Seattle, Columbus, Phoenix, Denver, San Jose, and San Francisco each completely removed SROs from their schools. In addition to the reductions in SROs in Chicago previously discussed, Los Angeles cut their school police department by a third,40 while Washington D.C. saw a 61% decrease in the number of SROs from 2020 to 2023.41 In sum, these removals and reductions following the summer of 2020 amounted to 346 fewer armed police officers and $81,859,403 fewer dollars spent toward SROs across these cities.42

Data from Minneapolis and Denver, two cities that completely removed SROs, shows promising impacts. In Minneapolis, the epicenter of the 2020 reform movements, law enforcement became involved in student discipline just 13 times in the 2021 fall semester compared to 250 times in the same 2020 semester when SROs were present. Further, although student disciplinary actions were declining even prior to the removal of school police, the 2021 fall semester saw 7 times fewer disciplinary actions taken than in the first half of the 2018-2019 year. In Denver, student referrals to law enforcement were down 81% in the 2021 school year compared to 2018.43

However, spikes in violence in schools have led to recent concerns in some cities where cops in schools were removed, including high numbers of school fights in Columbus44 and shootings outside high schools in Portland that led to talks about possibly bringing SROs back.45 3 of the 8 cities that removed SROs in 2020 (38%) have already since reinstated them. San Jose brought back their contract with local police for SROs in January 2022,46 and the Denver Board of Education voted to reinstate SROs ahead of the 2023 school year following a shooting of two administrators.47 Phoenix also reinstated SROs ahead of the 2023 year as part of a safety plan made after a large school fight broke out the prior year.48 Additionally, although D.C. has decreased the number of police in their schools substantially, their City Council originally planned to phase out all officers from schools by 2025 but reversed this plan in a recent vote following concern over juvenile crime and pressure from the Mayor.49

In addition to the cities that reduced and removed SROs, 7 cities (23%) left the number of police in their schools unchanged but made other substantive policy changes to their school discipline. For example, Philadelphia increased training requirements for SROs in 2020 to include adolescent development, de-escalation, and mentoring,50 while Oklahoma City rewrote SRO behavior expectations to include a smaller role in student discipline.51 In San Antonio, Care teams of mental health workers were created to step in during student mental health crises instead of SROs.52 Additionally, the Austin school district’s police department vowed to eliminate all student arrests and all use of force on students by the 2024-2025 school year.53

Washington D.C. schools also currently have over 300 unarmed security guards in addition to their armed SROs, and in 2020 control of these guards was transferred from the police department to the school district, with the district increasing training on youth development under this new plan.54 Although New York City initially passed a similar 2020 resolution that would have transferred control of SROs from the NYPD to the education department, this plan was reversed in 2022. However, after this reversal New York City pledged to increase the role of social workers in schools, create violence prevention programs, and reduce punitive responses to misbehavior.55

Three cities also responded to student petitions to remove cops in schools by announcing ‘rebranding’ of their school police, with ‘softer’ and more casual uniforms introduced in Boston, Philadelphia, and San Diego.56 Both Boston and Philadelphia also changed the name of their SROs from school police officers to ‘safety specialists’ and ‘school safety officers’ respectively.57 Students in Philadelphia pushed back with concerns that these uniform and name changes are surface-level only and do not target the deeper issues of school policing.58 Overall, 60% of the country’s top 30 cities saw some change around school policing following the summer of 2020, highlighting the influence of post-George Floyd activism in this policy area.

Spending on School Policing Today

In addition to the reforms around police in schools since 2020, we also tracked the current state of SRO spending across the top 30 cities. 9 cities did not have SRO budget data available, highlighting a need to further increase spending transparency nationwide. Of the 21 cities with data available, schools allocated an average of $100 per student to cops in schools. There was a wide range of spending, from cities who removed SROs spending $0 up to New York City spending $404 per student. As the graph below shows, Chicago’s $31 on SROs per student is the second least among the cities that still place officers in schools, only behind San Jose.

We also analyzed the top 30 cities’ spending on total school security, which includes SROs as well as unarmed security guards and school hardening measures like metal detectors and security cameras. Some schools have seen increases in their unarmed security guards as their SROs decreased, such as Columbus where the removal of armed school police was accompanied by the hiring of 20 additional unarmed security guards, also contributing to its importance in our analysis.59 Again, several of the top 30 cities did not have this budget data available, but of those that did, schools spend on average $212 per student on security. Interestingly, although Chicago ranks low in its SRO spending per student, its spending on total school security per student of $411 is the third highest nationwide, only behind San Antonio and Los Angeles (see below graph).

School Police and School Shootings

Lastly, we examined the impact of school shootings on school police policy across the top 30 cities. It is important to explore the effect of school shootings on school policing in particular, as conversations around cops in schools tend to spike following these tragic events amid calls for safer schools. School shootings have historically been catalysts for policy change, starting with the Columbine shooting in 1999 after which many laws targeting school safety were passed, most of which focused on preparing for shooting events, not preventing them.60 These measures prepared the school environment for an active shooter event, with school hardening measures like cameras and metal detectors as well as active shooter drills.61 Although the literature reveals no evidence that SROs deter gun violence in schools,62 school shootings tend to lead to increased police presence in schools, such as the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Act which followed the 2018 Parkland school shooting and required an armed police officer or guard in every Florida school.63

School shootings have also led to increased attention on SROs, both for positive action like in Santa Fe, Texas, where two officers confronted a school shooter with one losing his life,64 and for inaction, such as the Parkland shooting where an SRO was accused of staying outside the school and arrested for failing to protect students.65 In the 2022 school shooting in Uvalde Texas, the Chief of the Uvalde Consolidated Independent School District Police Department came under intense scrutiny for his department’s botched response to the shooting.66 In a tragic example of the policy cycle around school shootings, Uvalde had received $70,000 in grants for SROs and school hardening measures like cameras following the Santa Fe shooting as a preventative measure, leading some to question the prioritization of school security measures over gun control policies.67

This pattern of school shootings leading to increased calls for school security held true even after the 2020 advocacy movements to reduce police presence in schools. After the Uvalde shooting, 10 of the top 30 cities directly mentioned Uvalde as a catalyst for expanding or seeking to expand their school security presence. For example, following Uvalde, New York City dedicated an additional $48 million toward security cameras and door locks, Nashville allocated $6 million to fill SRO position vacancies and increase patrols of elementary schools, and Houston gave $2 million to their school police force to purchase more weapons. Further, both Fort Worth and El Paso saw calls to expand SROs to elementary schools after the shooting.68 One key finding of this report is how despite the empirical research showing cops in schools do not deter gun violence in schools, school shootings still serve as a catalyst for increased school policing across the country.

Our Recommendations

Chicago Justice Project supports Chicago’s decision to remove all SROs ahead of the 2024-2025 school year based on the research showing their null effect on school safety and negative impacts on marginalized students. However, the conversation on school discipline in Chicago must not end with the removal of cops in schools, so we present the following additional recommendations.

- Future research should examine school crime incidents in CPS schools before and after the removal of their SROs

- Based on research showing that when Chicago schools were trained in restorative justice, misconduct dropped 31% and suspensions dropped by 50%,69 CPS should follow through on its commitment to invest in restorative justice and other conflict resolution programs as an alternative to investing in school police

- CPS should reduce its use of school surveillance technologies and instead invest in counselors, social workers, and other mental health services

- Although CPS currently publishes data on student misconduct, suspensions, expulsions, and police notifications,70 and CPD provides monthly reports to the Board of Education on all school crimes, arrests made by SROs, and use of force incidents,71 CPD should increase transparency by routinely making student arrest data publicly available at the individual school level rather than just the police district level 72

- Future CPS budgets should include breakdowns of each component of “safety and security” funding, from the potentially-criminalizing X Ray machines and security guards to their crossing guards and clinician teams

While large strides have been made in Chicago since 2020 to decrease the role of cops in schools, future action is still needed to increase transparency, invest in students’ mental and emotional health, and end the school to prison pipeline. With the above policy changes, Chicago can continue to transform its schools to truly provide safety for all its students.

Citations

- Connery, C. (2020). The prevalence and the price of police in schools. UConn Center for Education Policy Analysis

https://education.uconn.edu/2020/10/27/the-prevalence-and-the-price-of-police-in-schools/# ↩︎ - Gottfredson, D., Crosse, S., Tang, Z., Bauer, E., Harmon, M., Hagen, C., & Greene, A. (2020). Effects of School Resource Officers on school crime and responses to school crime. Criminology and Public Policy, 19, 905-940. DOI: 10.1111/1745-9133.12512 ↩︎

- Theriot, M. (2009). School Resource Officers and the criminalization of student behavior. Journal of Criminal Justice, 37(3), 280-287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2009.04.008 ↩︎

- Javdani, S. (2019). Policing education: An empirical review of the challenges and impact of the work of school police officers. American Journal of Community Psychology, 63(3-4), 253-269. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12306 ↩︎

- Heitzeg, N. (2009). Education or incarceration: Zero tolerance policies and the school to prison pipeline. The Forum on Public Policy, 1-21. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ870076.pdf ;U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights. (2018). School Climate and Safety.

https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/school-climate-and-safety.pdf ↩︎ - Martinez-Prather, K., McKenna, J., Bowman, S. (2016). The impact of training on discipline outcomes in school-based policing. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 39(3), 478-490. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-02-2016-0022 ↩︎

- Laurence, J. (2021, September 22). CPS Board approves smaller contract to keep cops in high schools that want them. Block Club Chicago. https://blockclubchicago.org/2021/09/22/cps-board-approves-smaller-contract-to-keep-cops-in-high-schools-that-want-them/ ↩︎

- Jorgensen, J. (2022, September 7). Banks calls for more NYPD school safety agents. Spectrum News NY 1. https://ny1.com/nyc/queens/education/2022/09/07/banks-calls-for-a-safety-plan-for-nyc-public-schools ↩︎

- Issa, N. (2020, June 16). Aldermen, CPS students continue push for police-free schools: ‘You have a bad day, you get to go to jail?’. Chicago Sun-Times. chicago.suntimes.com/education/2020/6/16/21293262/aldermen-cps-students-police-schools-ordinance ↩︎

- Southorn, D. (2020, July 31). Chicago students organize to get cops out of schools. American Friends Service Committee. http://www.afsc.org/blogs/news-and-commentary/chicago-students-organize-to-get-cops-out-schools. ↩︎

- Issa, N. (2020). ↩︎

- Chicago Public Schools. (2020a, August 19). Chicago Public Schools proposes progressive reforms to School Resource Officer (SRO) Program based on feedback. http://www.cps.edu/press-releases/chicago-public-schools-proposes-progressive-reforms-to-school-resource-officer-sro-program-based-on-feedback/ ↩︎

- Kunichoff, Y., and Sabino, P. (2020, July 17). Some Chicago School Councils tasked with voting on police in schools aren’t following the rules. Block Club Chicago. blockclubchicago.org/2020/07/16/some-chicago-school-councils-tasked-with-voting-on-police-in-schools-arent-following-the-rules/ ↩︎

- Karp, S. (2020, August 17). Vote leaves Black students far more likely to have police in school than other teens. WBEZ Chicago. http://www.wbez.org/stories/vote-leaves-black-students-far-more-likely-to-have-police-in-school-than-other-teens/2cead960-176d-49e5-8db0-efb1147db39d. ↩︎

- VOYCE (2020). With parents, allies and elected leaders, VOYCE youth secure commitment for legislative action at city and state levels to transforming safety in our schools with H.E.A.R.T. https://communitiesunited.ourpowerbase.net/civicrm/mailing/view?reset=1&id=279 ↩︎

- Garcia, K. (2021a, July 21). More than 30 Chicago high schools will pursue alternatives to police. Injustice Watch. https://www.injusticewatch.org/news/2021/more-than-30-chicago-high-schools-will-pursue-alternatives-to-police-next-year/ ↩︎

- Amin, R. (2024, February 22). Chicago Board of Education votes to remove police officers from schools. Chalkbeat Chicago. https://www.chalkbeat.org/chicago/2024/02/23/chicago-board-of-education-votes-out-police-officers/ ↩︎

- Issa, N., and Karp, S. (2022, June 16). As cops leave Chicago public schools, staff move fitfully toward a new model of helping students. WBEZ Chicago. https://www.wbez.org/stories/as-cops-leave-chicago-public-schools-staff-move-fitfully-toward-a-new-model-of-helping-students/a759ff02-4386-43b2-a544-c87ffae3232d ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Chicago Public Schools. (2020b, August 10). Proposed CPS budget increases funding to support students during COVID-19 and invests equitably in neighborhood school modernization. http://www.cps.edu/press-releases/proposed-cps-budget-increases-funding-to-support-students-during-covid-19-and-invests-equitably-in-neighborhood-school-modernization/ ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Chicago Public Schools. (2020a) ↩︎

- Chicago Public Schools. (2021, January 26). CPS partners with five community groups to reimagine school safety strategies. www.cps.edu/press-releases/cps-partners-with-five-community-groups-to-reimagine-school-safety-strategies2/ ↩︎

- Garcia, K. (2021b, February 18). CPD rejects 70% of recommendations for SRO policy in Chicago Public Schools. The TRiiBE. thetriibe.com/2021/02/cpd-rejects-70-percent-of-recommendations-for-sro-policy-in-chicago-public-schools/ ↩︎

- Chicago Police Department (2020, November 5). SRO WG recommendations. https://www.chicago.gov/content/dam/city/sites/police-reform/CPD%20Responses%20to%20SRO%20CWG%20Recommendations%20-%20Appendix%202%20-%20Copy.pdf ↩︎

- Garcia, K. (2021b) ↩︎

- Chicago Police Department (2020) ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Issa, N. (2022, July 25). Chicago Board of Education to vote on new $10.2M school police contract. Chicago Sun-Times. https://chicago.suntimes.com/education/2022/7/25/23277463/cps-cpd-school-police-cops-officers-board-education-vote-contract ↩︎

- Amin, R. (2024) ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Chicago Public Schools Budget (2023-2024). p.144-148. https://www.cps.edu/globalassets/cps-pages/about-cps/finance/budget/budget-2024/docs/fy2024-budget-book-final-approved-1_1.pdf ↩︎

- Whole School Comprehensive Safety Plans. https://www.cps.edu/services-and-supports/student-safety-and-security/whole-school-safety-plans/ ↩︎

- Macaraeg, S. (2023, July 27). Chicago approves new X-Ray machines for public schools. Chicago Tribune. https://www.governing.com/education/chicago-approves-new-x-ray-machines-for-public-schools ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Graham, K.A. (2020, June 25). No more ‘police’ in Philly schools; ‘safety officers’ in new uniforms coming this fall. The Philadelphia Inquirer. https://www.inquirer.com/news/school-police-philadelphia-safety-officers-district-kevin-bethel-hite-20200625.html ↩︎

- Bazzaz, D. (2020, June 10). What we know about the effort to remove police stationed in Seattle schools. The Seattle Times. https://www.seattletimes.com/education-lab/what-we-know-about-the-effort-to-remove-police-stationed-in-seattle-schools/ ↩︎

- Gibbs, K. (2021, October 26). Community group wants to eliminate school resource officers. NewsChannel5 Nashville. https://www.newschannel5.com/news/community-group-wants-to-eliminate-school-resource-officers ↩︎

- Washington, A. (2020, July 3). AISD Hears Loud and Clear: No Cops in Schools. The Austin Chronicle. https://www.austinchronicle.com/news/2020-07-03/aisd-hears-loud-and-clear-no-cops-in-schools/ ↩︎

- Gomez, M. (2021, February 16). L.A. school board cuts its police force and diverts funds for Black student achievement. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2021-02-16/lausd-diverting-school-police-funds-support-black-students ↩︎

- Austermuhle, M. (2023, May 19). D.C. Council quietly backtracks on pulling police officers out of schools. DCIst. https://dcist.com/story/23/05/19/dc-schools-police-student-resource-officer-sro-fy24/ ↩︎

- Altavena, L. (2020, June 4). Students pressure Phoenix high school district to get police off campuses. AZCentral. https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/local/arizona-education/2020/06/04/students-push-phoenix-union-high-school-district-eliminae-campus-school-resource-police-officers/3145459001/ ;Bazzaz, D. & Furfaro, H. (2020, June 24). Police presence at Seattle Public Schools halted indefinitely. The Seattle Times. https://www.seattletimes.com/education-lab/police-presence-at-seattle-public-schools-halted-indefinitely/ ;Campuzano, E. (2020, June 5). Portland superintendent says he’s ‘discontinuing’ presence of armed police officers in schools. The Oregonian. https://www.oregonlive.com/education/2020/06/portland-superintendent-says-hes-discontinuing-school-resource-officer-program.html ;Harris, K. (2020, August 4). There’s a movement to defund school police, too. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-08-24/minneapolis-denver-and-oakland-defund-school-police ; Neese, A.W. (2021); Nguyen, T. (2021, August 12). Update: Largest San Jose school district brings back cops as security. San José Spotlight. https://sanjosespotlight.com/san-jose-school-district-considers-bringing-back-cops-as-security/ ;Rodriguez, O. (2020, June 24). As SF schools cut ties with police, state education chief says officers still needed in some schools. KQED. https://www.kqed.org/news/11825991/as-sf-schools-cut-ties-with-police-state-education-chief-says-officers-still-needed-in-some-schools ↩︎

- Asmar, M. (2023, January 17). Guns in schools are up, and Denver superintendent says violence is his top concern. Chalkbeat Colorado. https://www.chalkbeat.org/colorado/2023/1/17/23559733/denver-schools-youth-gun-violence-alex-marrero-top-concern/ ↩︎

- Henry, M. (2023, February 20). Assaults, guns, sex offenses among 5,202 ‘major incidents’ in 3 months at Columbus schools. https://www.dispatch.com/story/news/education/2023/02/20/assaults-sex-offenses-weapons-drugs-among-5202-major-incidents-in-columbus-schools-in-first-3-months/69865980007/ ↩︎

- Aldridge, A. (2023, February 14). Portland took cops out of schools in 2020. Now it may put them back. Truthout. https://truthout.org/articles/portland-took-cops-out-of-schools-in-2020-now-it-may-put-them-back/ ↩︎

- Magallon, S. (2022, December 15). Protesters demand SJUSD to have police-free schools, more mental health services. NBC Bay Area. https://www.nbcbayarea.com/news/local/protesters-san-jose-schools-police/3106804/ ↩︎

- Cook, L.L. (2023, June 15). Denver School Board votes to reinstate school resource officers. KDVR. https://kdvr.com/news/local/denver-school-board-votes-to-reinstate-school-resource-officers/ ↩︎

- McCall, J. (2023, June 1). Phoenix Union High School District passes new safety plan featuring school resource officers. 12News. https://www.12news.com/article/news/education/phoenix-union-high-school-district-return-of-school-resource-officers-on-campuses/75-21d615b9-ef3a-4cbb-bc61-ec09a2630b00 ↩︎

- Austermuhle, M. (2023) ↩︎

- Miller, A. (2020, June 26). Philly schools’ plan to rebrand police as ‘safety officers’ draws ire of student union. Philly Voice. https://www.phillyvoice.com/philadelphia-school-district-police-safety-officers-uniforms-student-union/ ↩︎

- Dickerson, B. (2021, June 29). OKCPS to spend $2 million on revamped school resource officer program. Oklahoma City Free Press. https://freepressokc.com/okcps-to-spend-2-million-on-revamped-school-resource-officer-program/ ↩︎

- Donaldson, E. (2020, June 10). Letter Calls on San Antonio ISD to Reevaluate School Police Funding. San Antonio Report. https://sanantonioreport.org/defund-the-police-san-antonio-independent-school-district-police-department/ ↩︎

- AISD Goals. https://www.austinisd.org/sites/default/files/dept/police/docs/KPI_1.pdf ↩︎

- Gomez, A. M. (2020, June 26). D.C. Council moves to cut some ties between police and schools. Washington City Paper. https://washingtoncitypaper.com/article/304069/dc-council-moves-to-cut-some-ties-between-police-and-schools/ ↩︎

- Jorgensen, J. (2022) ↩︎

- Daniel, S. (2021, July 15). Boston School Police quietly phased out from all BPS schools. The Boston Sun. https://thebostonsun.com/2021/07/15/boston-school-police-quietly-phased-out-from-all-bps-schools/ ;Huntsberry, W. (2021, October 21). The learning curve: Whatever happened to San Diego Unified Police Reform? Voice of San Diego. https://voiceofsandiego.org/2021/10/21/the-learning-curve-whatever-happened-to-san-diego-unified-police-reform/ ;Miller, A. (2020) ↩︎

- Daniel, S. (2021); Miller, A. (2020) ↩︎

- Miller, A. (2020) ↩︎

- Morgan, T. (2021, August 17). Columbus City Schools to start new year with 100 plus safety officers. ABC 6 Columbus. https://abc6onyourside.com/news/local/columbus-city-schools-to-start-new-year-with-100-plus-safety-officers ↩︎

- Temkin, D., Stuart-Cassel, V., Lao, K., Nuñez, B., Kelley, S., & Kelley, C. (2020, February 12). The evolution of state school safety laws since the Columbine school shooting. Child Trends. https://www.childtrends.org/publications/evolution-state-school-safety-laws-columbine ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Javdani, S. (2019) ↩︎

- ACLU Florida (2020, September 2). New study reveals Florida’s school policing mandate has increased negative outcomes for students. https://www.aclufl.org/en/press-releases/new-study-reveals-floridas-school-policing-mandate-has-increased-negative-outcomes ↩︎

- Becker, A. (2019, February 1). Santa Fe Survivor: Inside the race to save Officer John Barnes. Texas Medical Center. https://www.tmc.edu/news/2019/02/santa-fe-survivor-inside-the-race-to-save-officer-john-barnes/ ↩︎

- Kramer, M., and Harlan, J. (2019, February 13). Parkland Shooting: Where gun control and school safety stand today. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/13/us/school-shootings-parkland.html ↩︎

- Goodman, J. D. (2022, June 9). Aware of injuries inside, Uvalde Police waited to confront gunman. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/09/us/uvalde-shooting-police-response.html ↩︎

- Smith, C. (2022, May 25). Texas was supposed to make schools safer to stop another shooting like Uvalde. The Dallas Morning News. https://www.dallasnews.com/news/education/2022/05/25/texas-was-supposed-to-make-schools-safer-to-stop-another-shooting-like-uvalde/ ↩︎

- Carrillo, J. (2022, August 15). El Paso police, EPISD police could collaborate to bring more resource officers. KFOX14. https://kfoxtv.com/news/local/el-paso-police-episd-police-could-collaborate-to-bring-more-resource-officers-uvalde-schools-education-safety-manuel-chavira-endependent-school-district-city-texas ;Collins, L. (2022, June 8). Fort Worth City Council members concerned due to lack of elementary School Resource Officers. NBCDFW. https://www.nbcdfw.com/news/local/fort-worth-council-members-concerned-due-to-lack-of-elementary-school-resource-officers/2987473/ ↩︎

- Black, C. (2020, June 11). What’s the alternative to police in schools? Restorative justice. The Chicago Reporter. https://www.chicagoreporter.com/whats-the-alternative-to-police-in-schools-restorative-justice/ ↩︎

- Chicago Public Schools. “Metrics”. https://www.cps.edu/about/district-data/metrics/ ↩︎

- Intergovernmental Agreement Between the City of Chicago and the Board of Education of the City of Chicago. (2022). https://www.cps.edu/globalassets/cps-pages/about-cps/department-directory/office-of-school-safety-and-security-osss/2023-cps-cpd-sro-iga_.pdf ↩︎

- Project Nia (2012). Policing Chicago Public Schools: A gateway to the school-to-prison pipeline. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/519b9f87e4b09ffb7ee392b2/t/519baeb3e4b057d5f788a09f/1369157299813/policing-chicago-public-schools.pdf ↩︎