This issue brief covering the topic of domestic violence and domestic related calls for service was completed in collaboration with the Chicago Metropolitan Battered Women’s Network.

Chicago Police Superintendent Jody Weis was quoted in May 2010 as saying that he believes the Chicago Police Department (CPD) can prevent “outdoor” homicides, but when murder happens inside, “it’s hard for police to have an impact on that.” Weis says that he wishes CPD could prevent homicides that happen indoors but he just does not see how his officers can do that.

What the public might not realize is Chicago Police have been told precisely how they can prevent “indoor” homicides. Consider the brutal murder of Ronyale White in May 2002. White was a victim of domestic violence who had an order of protection against her husband. The night she died, White called 911 no less than four times to report that her husband was threatening her with a gun and she feared for her life. The police officers that were called for service chose to make calls on their personal cell phones and listen to voicemails and their response only came after Ms. White had been murdered in a very preventable “indoor homicide.”

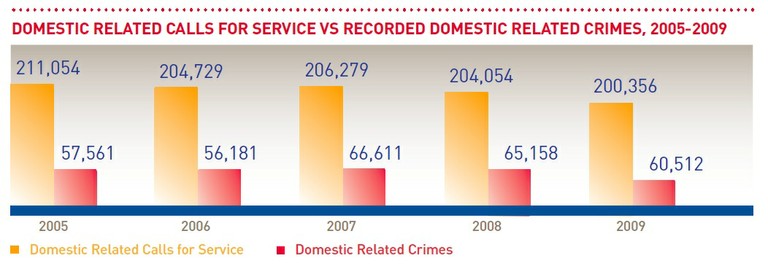

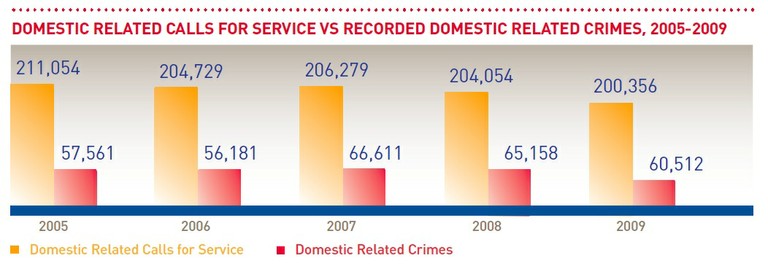

The Chart below details the number of calls for service the Office of Emergency Management and Communications (OEMC) receives per year that are domestic related. The red bar shows the number of domestic related crimes the Chicago Police Department recorded per year.

Facts about the numbers of domestic related calls, 2005-2009

- Total number of calls for which a police report was not generated: 720,449

- Average number of calls per year for which a report was not generated: 144,090

- Percentage of calls per year that do not result in a report being generated: 70%

The Recommendation

A return rate of 9.7% leads to questioning data collection practices

Originally The Network and CJP set out to determine how many of the domestic related homicide victims in 2009, 34, had previously called for service for abuse prior to the incident that resulted in their deaths. The Network has consistently been told by police officials that the majority of domestic homicide victims have never called for police services prior to the murder by police officials. A simple enough task we thought, compare OEMC data on calls for service vs. the location of domestic homicides and the names of victims. Well, it is not so simple if you are dealing with a criminal justice system that is as closed to public scrutiny as the Chicago criminal justice system is.

In partnership with the Civil Rights Clinic of DePaul University College of Law, law students requested information under the Illinois Freedom of Information Act from both the CPD and OEMC. Both agencies to one degree or another resisted the release of information related to domestic homicides and domestic related calls for service.

- The CPD did eventually release police reports related to all 34 domestic homicides that occurred in Chicago in 2009. We were able to determine that the 34 homicides occurred in 31 incidents that contained specific address locations of the homicides. The CPD did redact a significant amount of information from the reports, like the code the officers put in the reports to signify the relationship between the deceased and his/her killer. They also redacted many of the names of perpetrators. CJP interns researched each murder and identified many of the names of the perpetrators from press reports that were conducted at the time of the homicide. Basically, the CPD’s practices, which are completely opposite of the letter and spirit of Illinois’ new Freedom of Information Act that went in to affect on Jan 1st of 2010, were futile because the press had already identified the individuals at the time of the homicides or shortly there after and prior to the CPD redactions.(A copy of the report is available here.)

- In the DePaul Law Students FOIA request to OEMC they asked for all publicly available data for domestic related calls for service for the year 2009. OEMC resisted by saying that this request was overly burdensome. After the students reduced the time period covered under the request, OEMC still was not forth coming with data. The fact that OEMC would request that the students reduce the time period covered by the request is counter-intuitive because all the data must be digitally maintained meaning that the difference between 6 months of data and 12 months can only be a few keystrokes. It is obvious that the new FOIA law has not permeated the practices of local agencies as much as citizens would have hoped.

In the end CJP submitted a new request under Illinois’ Freedom of Information Law with OEMC after taking the address for the 31 locations of the domestic homicides from the Chicago Police Department reports CJP submitted those to OEMC and asked the agency to please provide information on all calls for service related to those addresses from 2006-2009. OEMC responded by providing that information as requested. The problem? Of the 31 sites listed as locations for domestic homicides where police and ambulances responded only 3 of those locations listed calls for service related to the homicides, a sparkling 9.7% return rate.

Conclusion

This seemingly glaring failure of OEMC to locate calls for services for 90% of the domestic related homicides is very troubling and certainly throws the claim by the CPD that domestic homicide victims have never called for service prior to their homicides into doubt. With these kinds of inadequacies in data collection, we find it hard to believe how any reliable policies could be based off of OEMC data. Both CJP and The Network believe that a review by both OEMC and the CPD of the discrepancy is in order. The citizens of Chicago deserve nothing less than agencies that collect, maintain, and release data in accordance with the best practices from across the nation. We find it hard to believe that a 9.7% return rate on calls for service to domestic related homicides is the best that the Chicago criminal justice system can produce.

Calls for Service: Anytime the CPD or the Chicago Fire Department are dispatched a call for service is logged with OEMC and then OEMC dispatches police, fire, or both. CJP checked with a police source to see what aspects of the calls for service we were missing. That source informed CJP that the main way that a domestic homicide location might not come up in OEMC data is if the police officers were dispatched to a hospital and not the specific location of the homicide. CJP reviewed all 31 police reports and confirmed that for each domestic homicide in Chicago in 2009 the officers responded to the location of the homicide and not a local hospital.

Marry this extremely low return rate with the fact that the CPD averages 144,090 domestic related calls for service a year that go without a police report being generated and you have the perfect storm of data issues. On one end, the CPD is not generating reports to track how responding officers handle most domestic related calls for service while on the other end even when the CPD does generate reports OEMC fails to collect data consistently to allow community members or advocates to track police and OEMC responses to domestic related calls. Clearly only a new prioritization of data collection practice by both OEMC and the CPD regarding domestic related calls for service will alleviate this problem.